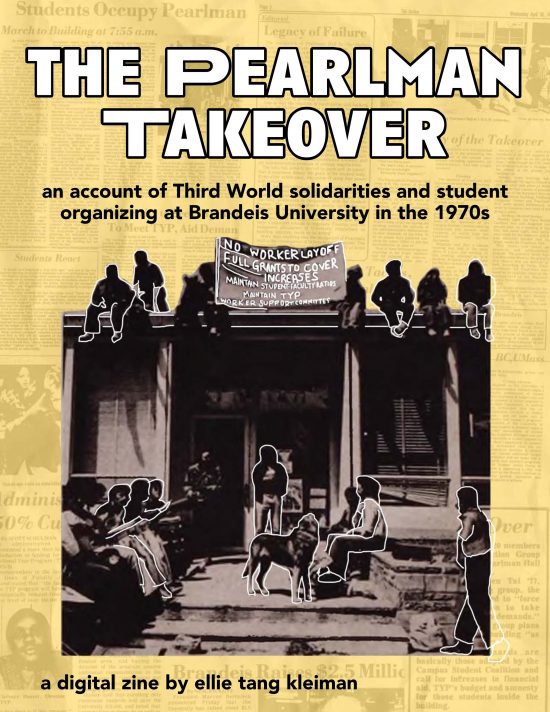

An account of Third World solidarities and student organizing in the 1970s

Introduction

On April 29th 1975, Brandeis University students initiated the six-day takeover of Pearlman Hall, the building home to the Sociology Department on campus. This multi-racial group of students, who called themselves the “Student Action Group” or “SAG”, presented a list of demands to the administration concerning the inclusion of Asian Americans in the minority financial aid pool, a proportional increase in that pool, an end to faculty layoffs, reversing cuts to the Transitional Year Program (TYP) budget, no worker firings to obtain money to meet the other demands, and total amnesty for those inside the building. This brief and long-forgotten incident in the university’s history reveals much more than a week-long protest, but over three years of collective organizing, multi-racial solidarity, imaginative militancy, and the carving of a liberatory space by low-income students of color in an institution that was never meant for them. My hope in recounting the Pearlman Takeover and the organizing that led up to it is that students and administration alike learn from and remember the repeated patterns of oppression in the university’s history that have the potential to be challenged and overturned by student power.

Part 1: The Third World Coalition

In the early 1970s, students of color on the Brandeis campus forged a strong political identity that followed in the footsteps of the Black students who occupied Ford Hall in 1969, and that was linked to the emergence of national movements and groups such as the Third World Coalition, the Third World Women’s Alliance, the Combahee River Collective, and the anti-war movement. For example, the Brandeis Asian American Students Association (BAASA) led campus dissent against the war in Vietnam and American imperialism, organized Brandeis (specifically, Professor Fellman’s Pearlman office) to be the headquarters of the National Student Strike in May 1970, and participated in demonstrations and community work in Boston’s Chinatown. The Afro-American Organization (Afro) continued to hold the administration accountable to Ford Hall demands by pushing for changes in admission procedures and increased scholarships to Black students. Grito, the organization of Puerto Rican and Mexican American students, organized a strike of Kutz dining hall alongside the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee demanding that Brandeis only serve union-picked lettuce and organized alongside Afro regarding admission procedures.

In February 1972, students of BAASA, Grito, and Afro held a demonstration protesting cuts in financial aid allocated to minorities. By December 1972, these three groups had formed the Third World Coalition (TWC) and brought forth their unified demands to a meeting with President Marver Hillel Bernstein. In the spring of 1973, it was revealed that the administration failed to meet the demands–instead of doubling the minority financial aid pool from $100,000 to $200,000 as the TWC had asked, they only increased the pool to $110,000.

Administration also rejected the demand to include Asians in the minority financial aid pool, stating that “The Faculty Committee on Admissions and Financial Aid finally decided that the inclusion of Asian students would, in effect, force out other minority students because Asians generally have stronger academic records. The committee thought Asians ‘do well enough’ on their own in applying to Brandeis”. It is likely that in making this statement, the committee was thinking exclusively of Asians from privileged backgrounds who encompassed the “model minority”, a racial construction of Asian Americans as “distinct from the white majority, but alluded as well assimilated, upwardly mobile, politically nonthreatening, and definitively not-black” (Wu 2). The “model minority” myth and the administration’s statement erase the majority of Asian Americans who do not fit neatly into this definition, such as those who are working class, politically conscious, mixed-race, or darker-skinned/non-East Asian.

The administration’s response prompted the TWC, the following spring, to publicly release a list of demands and hold a “Third World Teach-In” in late March. Their list of demands included:

- The financial aid grants for full need, low income students, should be raised from $3700 to $3900

- That TW attrition monies should go towards the admissions of TW transfers and freshmen

- That Asians be considered part of the TW students

- That the minority pool funds should be increased from $110,000 to $200,000 for the following reasons:

- In order that Asians may be included in the minority aid pool

- In order that the $300 increase in tuition and room and board be compensated for in grant

- In order that the TW community be restored to the previous level of 1971-72

- That the University specifically define their position as regards Brandeis’ commitment of $400 in work, with the additional possibility of work-study equal to or above this year’s allotment

- That, because of yearly ambiguity over financial aid and admission of TW students, the University hereby fix policy to establish low income grants at 87% of the total tuition, room and board, for full need students

Just days after the Third World teach-in, on April 2 1973, the TWC took over the Bernstein-Marcus administration building, barricading doors and covering windows, while a Grito representative presented demands at a rally outside of the building. The takeover ended that evening when the university threatened to prosecute the students inside. As the school year came to a close, five Latino and African American students were subjected to an aggressive disciplinary process due to their participation in the takeover. None of the TWC demands were met.

!["Unite to Support the Three Just Demands of the CSC!" [student pamphlet cover, undated]](http://blackspaceportal.library.brandeis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/GFF006UniteToSupportCSC1-550x715.jpg)

Part 2: The Campus Student Coalition

Two years later, in the spring of 1975, the administration announced a cut to more than 50% of the Transitional Year Program (TYP) budget from $80,000 to $35,000. Ironically, this announcement was published on the front page of the March 4,1975 edition of The Justice right next to an article titled “Brandeis Raises $2.5 million of Unrestricted Income”. Days after the TYP cuts were announced, representatives of Afro, BAASA, Grito, the United Farm Workers Support Committee, the Women’s Coalition, and the Waltham Group formed a group called the Campus Support Coalition (CSC). The first meeting was promptly held to establish demands, many of which were adopted or adapted from the TWC demands two years prior, and with some additions including the end to faculty layoffs and no worker firings to meet the demands.

The CSC kicked off a week of direct action on March 11, 1975, which consisted of marches, sit-ins, and letters to administration leading up to the Board of Trustees meeting at the end of the week. Yet, the week ended in frustration when the Board of Trustees announced it was unable to meet the CSC’s demands, and resulted in an argument between the “moderates” and “activists” among the CSC, and some of the “activist” members split off from the group. Nevertheless, CSC efforts continued throughout April, with the publication of a weekly independent newsletter and a boycott of lunch at Kutz dining hall in support of CSC demands.

Part 3: The Pearlman Takeover

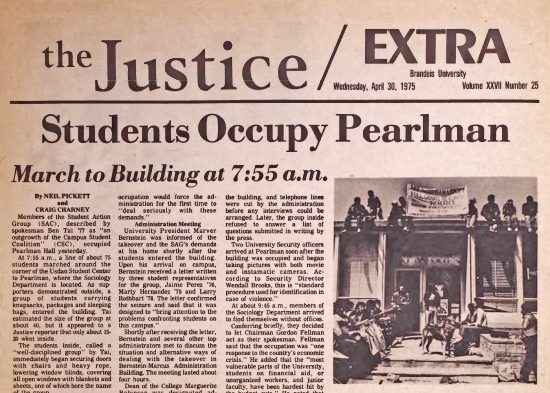

As the end of the 1974-75 school year approached, some former CSC “activists” decided to take matters into their own hands. At the end of April, students formed the Student Action Group (SAG), endorsed by the Third World Coalition, and took what some members identified as purposefully militant and disruptive action to occupy Pearlman Hall. SAG intended the occupation to send a clear message to the university administration to take their demands seriously. On April 29th 1975 at 7:55am, a group of 28 anonymous students entered Pearlman Hall carrying “knapsacks, packages, and sleeping bags” (a conversation on July 14th, 2020 with alumni Ben Tai ‘76 reveals that students inside the building brought art supplies with them to create signs and posters for use outside the building). The doors of the building were immediately secured with chairs and ropes.

Pearlman Hall was chosen for a number of reasons: it was central to campus layout, it had symbolic significance as it was used as the National Student Strike Headquarters five years prior, and many of the student organizers were sociology majors therefore they knew both the building and its faculty very well. In fact, secret negotiations were made with sociology faculty prior to the takeover to ensure that they were fine with their offices being inaccessible for the week. Recently, Professor Gordon Fellman casually reminisced that his only ask of the students was that they water his plants while inside (which they did). Fellman and four other sociology faculty members served as liaisons between the administration and students during the takeover.

The first day of the sit-in was quite eventful: after Tai announced the demands on the campus radio (which were the same as CSC’s demands with the added condition of amnesty for those inside the building), a group ranging in number from 50-175 students marched, chanted, and rallied outside the building expressing solidarity with those inside and with the protest activities occurring at Boston College, UMass, and Brown at the same time. The spokespeople and “faces” of the group who led activities from outside the building were students Ben Tai, Jaime Perez, Larry Rothbart, and Martha Hernandez. The spokespeople made clear that students would not leave the building until demands were met, even in the face of the university’s immediate threat to use force to dislodge students in seeking a court injunction. A recent account from Tai reveals that the National Lawyers Guild helped students take the university to court and file a Temporary Restraining Order, which was overturned within days, but allowed the students to stall the university and remain in the building for longer.

Throughout the six days of the takeover, while juggling legal hurdles and negotiations with the administration, SAG held rallies and teach-ins outside of Pearlman that drew large crowds. There were teach-ins about May Day on May 1st and on the Vietnam War and US imperialism, given that the fall of Vietnam occurred on the first day of the takeover.

The final two days of the takeover consisted of intense negotiations between the administration and Tai, Perez, and Rothbart. Although the demands were not fully met, the university made significant concessions. The administration agreed to increase the TYP budget to $52,000 rather than the originally budgeted $35,000, to set a “floor” on the grant proportion (not let the proportion of grants go below the 1974-75 level), to set an intent to increase the grant proportion by 1976-77, they indicated that they would not terminate any workers for supplemental funds, and committed to the employment of current students to assist in the recruitment of low-income and minority students. By the end of negotiations, the university acknowledged and committed to “study and report on” the concern about financial aid for Asian Americans, but it wasn’t until the following fall that Asians were officially recognized as a minority group eligible for minority financial aid. Despite President Bernstein’s repeated claims that “no real concessions were made”, there was no denying the university’s shifted stances on many fundamental issues. Immediately after these concessions (or “shifted stances”) were confirmed, on May 5th 1975 at 12:10am, a group of 25 students entered the building and exited alongside the 28 occupying students to maintain the anonymity of the occupiers.

!["Continue the Fight- Build the Student Union!" [student pamphlet]](http://15.222.11.18/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/GFF010ContinueThe-Fight1-550x680.jpg)

Part 4: Aftermath

In the weeks following the end of the takeover, students gathered in an assembly of over 400 students and agreed on the establishment of the Student Union, with the purpose of being a “permanent defense organization” to defend students’ rights, including the right of all people to an education, the right of students to organize, and the right to have a role in budgetary and other University decisions. Students also held a rally to demand that President Bernstein address the student body in a convocation, to clarify the agreements made after the Pearlman Takeover. A group of 55 students walked to his house and “received 5 police cars and a closed house as a response to the attempt at clarifying the issues”. In a pamphlet found in the University Archives, the new Student Union rearticulated the need for students to continue to organize, work and struggle, and also celebrated the students’ victory:

“We have achieved the most difficult task – we have organized the campus! A multi-ethnic movement has brought this campus closer to a real integration of sectors and ideas. This is a REAL VICTORY! President Bernstein and all administrators know they will have to listen. They dread the idea of a multi-ethnic united movement.”

Today’s Takeaways

The campus of Brandeis University today faces a crisis of the university’s persistent marginalization of BIPOC low-income members of its community. Through incidents like the Pearlman Takeover, the archive reveals that this is not a new crisis, but rather a very old one that has repeated throughout history since the university’s founding. Though the university prides itself on “progress” and “social justice” enacted through its task forces, memorandums, and solidarity statements throughout the years, the surface-level nature of these actions is laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic and the precarious situations that BIPOC low-income students find themselves in today. Whether it is the over-policing of Black students making them feel unsafe on campus, the lack of support given to the Intercultural Center and Black/Brown-led student organizations, the lack of diversity in the Counseling Center, the retention of racist administration staff and faculty, the lack of accountability for dining workers’ pay and benefits, the significant cuts to financial aid packages in the middle of a pandemic, or a racist protest policy, Brandeis has a long way to go before BIPOC low-income students will feel safe and welcome on campus. A useful course of action for students who are affected by these conditions and seek to change them may be to look back in history for valuable lessons to be learned from those who organized resistance in protest of similar conditions on this campus in the past.

Resources at Brandeis

There were several resources used by the author to research this article, and we highly recommend them to our readers. For assistance in accessing these resources and more please contact Archives & Special Collections.

Student Activism at Brandeis collection

Transitional Year Program collection

The Justice [student newspaper]

Additional Resources

Pai, Sunny. Interview by Ellie Tang Kleiman. 10 July 2020.

Tai, Ben. Interview by Ellie Tang Kleiman. 14 July 2020.